Pharmacy Matters, Family Matters: Pharmacy Matters, Family Matters:

Game-changing ‘Charlie’

...Beloved administrator retires after four decades

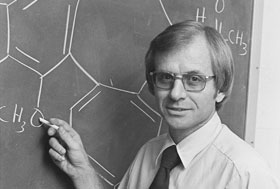

Charles D. Hufford

t was 42 years ago when Charles D. Hufford first climbed the stairs to his new office on the fourth floor of Faser Hall, home to the University of Mississippi’s School of Pharmacy. The then-new Ohio State University Ph.D. graduate had no clue that, more than four decades later, his UM colleagues would credit him with helping transform their pharmacy school into one of the world’s powerhouses in his field – the study of natural compounds – or for vastly enhancing and equipping it for education and research.

But that’s exactly what his colleagues say Hufford has done.

“Charlie’s low-key but effective leadership over several decades really helped shape and preserve our natural products legacy, even though he stayed pretty much in the background as far as any great fanfare goes,” said Larry Walker, director of the school’s world-renowned National Center for Natural Products Research.

Hufford “was a key player over many years in growing our culture for research,” said Barbara G. Wells, who, as the school’s dean, worked with him for a decade.

“He was always available to faculty to help them strengthen their own research programs,” she said. “He deserves our unending gratitude for his teaching, research, mentorship and administrative leadership.”

Hufford has spent his entire career helping to make the School of Pharmacy succeed and “be a great place to work,” said Alice M. Clark, UM’s vice chancellor for research and sponsored programs.

“His accomplishments were so foundational and steady that they rarely drew much attention, but his quiet fortitude and commitment to excellence have been major factors in the school’s success over the past 40 years,” she said. “He was instrumental in building the infrastructure that was needed to allow the school to become first in the nation in natural products research and consistently among the top in research overall.”

Hufford, who began his career here as an assistant professor of pharmacognosy in 1972, became his department’s chair in 1987 and his school’s first associate dean for research and graduate programs in 1995. He also thrice served his department as acting chair, first in 1977, only five years after joining its faculty, again in 1985, and yet again (1995-99) while associate dean.

He is retiring Feb. 1.

“We have been incredibly lucky to have Charlie as a faculty member and administrator,” said David D. Allen, the school’s dean. “He has made a huge impact on the school, and he will leave big shoes for our next associate dean to fill.”

Impressive record

Hufford (left) and other pharmacy school leaders sign a column in the new addition to the National Center for Natural Products Research.

Hufford, who has worked under four pharmacy school deans, began garnering their respect and that of his colleagues in the early ’80s, when he and Clark, his wife, then an assistant professor of pharmacognosy; John K. Baker, then professor of medicinal chemistry; and James D. McChesney, then professor and chair of pharmacognosy, took the drug primaquine back into the laboratory to try to remove its side effects. Their efforts were based on the notion that one of the drug’s metabolites was causing its side effects, and another was killing Plasmodium vivax, the culprit behind relapsing malaria.

With Clark feeding primaquine to select microbes and Hufford and Baker identifying structures of the metabolites they produced, the researchers found primaquine’s major metabolite, and it was one that hadn’t even been considered by other researchers.

“Charlie and one of his graduate students were the first to prove the postulation that microorganisms could be used as models of human drug metabolism,” Clark said. “Their work showed that microbes could produce the same metabolites of tricyclic antidepressants as humans.”

It was that work, she said, that led to the identification of carboxyprimaquine.

“Primaquine had been used clinically for decades, and researchers understood it was extensively metabolized, but the identity of the major metabolite had eluded everyone. This discovery was perhaps the first example of using microbes to guide the search for a human metabolite.”

Subsequently, the foursome published a paper detailing the mammalian metabolism of the isomers of primaquine.

“Charles was highly accomplished in many areas of pharmaceutical research, but his efforts most brightly shined in the area of drug metabolism,” Baker said.

But Hufford’s efforts didn’t stop there.

By 1984, he and his colleagues were routinely determining whether plant and other extracts killed or inhibited the microorganisms that cause bacterial and fungal infections. To do so, they simply added them to flasks or petri dishes in which colonies of the pathogens were established, then watched to see what happened.

After adding an extract from the heartwood of a tulip poplar tree, Hufford said, “there was nothing on the plate, so we thought somebody messed up. We tested it again and found that it inhibited everything on the plate.”

Subsequent work by Hufford revealed the compound responsible for the extract’s antibiotic effects was liriodenine, which he patented.

Because of their proven ability to find and characterize potent new antifungal antibiotics, Hufford and Clark received $500,000 from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, or NIAID, to screen compounds for activity against opportunistic infections threatening the lives of AIDS patients in 1984. With that grant, they found a group of potent antifungal antibiotics called sampangines.

With that progress, the pharmacognosy duo received a $1 million contract renewal in 1987 and a $372,000 grant from NIAID in 1989. That grant was renewed four times and became one of the longest continually funded antifungal research programs in NIH history, brought $7.4 million to UM and led to the identification of many new natural products.

Hufford also supervised work to determine the sampangines’ chemical structures with the aid of the school’s new high-field nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer, then the only one of its kind in Southeastern pharmacy schools.

Hufford helped acquire the NMR spectrometer and got it operating. He also became the “go-to guy” for interpreting the tremendous amount of data it yielded for compounds rising through the school’s drug-discovery program.

Helping establish the school’s NMR capabilities was another feather in Hufford’s research cap.

“Charlie has a gift for the acquisition and interpretation of NMR spectral data for structure elucidation of novel natural products,” Clark said. “Through his leadership and expertise, our reputation for isolating and identifying complex natural products was established, and this, in turn, helped cement our leadership in natural products.”

Today, the school has six NMRs, and it’s trading one of them in and buying three more. As a research scientist, seeing the school go from one NMR to eight is one of the most rewarding things to happen to Hufford during his Ole Miss career.

“What this means,” he said, “is that our drug- and agrichemical-discovery programs have grown so much that we need that many.”

Mr. Administrator

In 1999, Hufford proudly watched as Clark, then director of the National Center for Natural Products Research; Kenneth B. Roberts, the school’s dean; and other Ole Miss officials dedicated the Thad Cochran Research Center, NCNPR’s new home. Although the center provided an impressive suite of offices for the school’s dean, other administrators and their support staffs, most of its academic and other research enterprises remained in Faser Hall, which was constructed 30 years earlier and needed to be expanded and modernized. Lamenting that fact, Roberts asked Hufford to “get Faser redone.”

The project would require more than $10 million, but it was launched in 2000, thanks to a $1 million grant from NIH. The grant application, which Hufford wrote, received a score of 120 on NIH’s scale of 100 to 500, with 100 being superior.

“That meant our proposal ranked in the top 2 (percent) or 3 percent among all those received from around the country,” Hufford said. “That said a lot about the quality of research conducted by our faculty.”

With that initial funding, the school began constructing what would become a 10,000-square-foot structure at the rear of Faser Hall to house faculty and staff as their floors were being renovated. This “swing space” was used several times in ensuing years for that very purpose.

At the same time, construction of NCNPR’s 96,000-square-foot addition (Phase II, or west wing) was “always on the drawing board,” Hufford said. Before construction could begin, however, the school had to accumulate the funds to pay for it. To obtain them, Hufford wrote five proposals and portions of a sixth.

The first five secured $14.4 million from the Health Resources and Services Administration to plan and build the west wing and Centennial Auditorium that connects it to the Cochran Center and Faser Hall. One of the HRSA grants also provided both buildings with some essential instrumentation. The sixth, with Walker as the principle investigator, secured the $13.9 million from NIH that made completion of the west wing possible.

While funds were trickling in, Hufford worked with architects to plan and design the facilities and with contractors to get them built. Getting all this done in multiple stages over some 14 years while maintaining the school’s high standards for research, teaching and service would have been a logistical nightmare for many. It wasn’t for “Charlie.”

As the school’s “externally funded program and building guru,” he helped lead the pharmacy school’s transformation from two buildings to “a complex,” said architect Robert E. Farr II of Cooke, Douglass, Farr and Lemons, which designed the Faser renovations, auditorium, west wing and Maynard F. Quimby Medicinal Plant Garden.

“Charlie had to be ‘Mr. Building,’ ‘Mr. System,’ ‘Mr. Mechanical,’ ‘Mr. Electrical’ and ‘Mr. Laboratory Planner,’ as well as a psychologist, social worker, negotiator, counselor and scribe, who kept all the records of the steps and actions required to achieve the school’s transformational plan,” Farr said.

Hufford is proud of the school’s transformation and his part in it, although it was “years in the making,” he said. Among the features he likes most about the complex is the walkway across the top of the auditorium that connects NCNPR’s east and west wings, facilitating collaborations among researchers.

“The other big thing,” he said, “are the spacious and flexible labs, which will enable research growth for years to come.”

The right stuff

Hufford is as accomplished in the classroom as he is in the laboratory and administrative suite. As professor and chair of his department, for example, he revamped the pharmacognosy course for students in the school’s professional program by including information on dietary supplements and making it more contemporary and relevant to pharmacy practice.

“This adaptation turned out to be almost prescient because, within about a decade, the U.S. Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act,” Clark said. “We were one of the few schools in the nation with the faculty and infrastructure ready to prepare pharmacists for the vitally important role of counseling patients about these products.”

Hufford also developed and taught an elective about herbal products for professional students.

“It is a very popular course,” said Marvin C. Wilson, associate dean emeritus for academic and student affairs.

Hufford is “an excellent classroom teacher who delivers challenging concepts with ease and clarity,” said one of his former graduate students, Ehab A. Abourashed (PhD 98), now an associate professor of pharmaceutical sciences at Chicago State University. “He also has been successful in mentoring and supervising graduate students who have achieved success as academicians, researchers and pharmacy professionals, wherever their career paths led them.”

Ensuring that the quality of the school’s graduate programs was maintained and enhanced was “always a ‘front-burner item’ for Charlie,” Wilson said.

The number of students enrolled in these programs grew remarkably on Hufford’s watch, as did extramural funding for the school’s research, training, service and construction projects. While associate dean, Hufford kept tabs on more than $314 million.

Walker said Hufford’s “steady, patient and focused leadership, even in difficult situations,” enabled him to accomplish such things.

“Charlie is a rare breed,” Walker said. “He is a perfectionist – very meticulous and organized. Yet he is pretty laid-back in dealing with others and, for the most part, unflappable.”

Wells said it’s because “Charlie is highly intelligent, intellectually curious and persistent and tenacious in pursuit of his objectives. He also has good interpersonal skills and knows how to collaborate with others to achieve complex goals.”

Jean Pinion, Hufford’s administrative assistant of 18 years, said it’s also because he “has so much common sense” and “is so knowledgeable and trustworthy.”

“He’s a great boss, but he always treats me as an equal,” she said. “There were times when he and the dean had to be away, and I had to make decisions. When I did, I knew he always had my back. He trusted me, and I trusted him.”

Lighter side

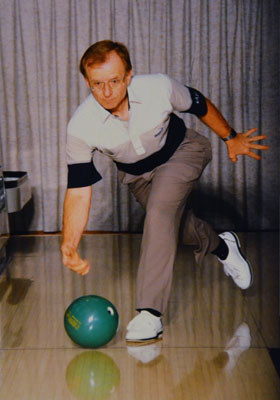

Yes, “Charlie can be a ‘bird dog’ about things,” Wilson said. “He is committed to everything he does, and his commitment to excellence is unwavering,” which explains why Hufford is an exceptionally competitive bowler. He bowled his first perfect 300 game at age 38.

“It was at Kiamie’s, Dec. 14, 1982,” Hufford said. “It was the first 300 game ever bowled in Oxford. It took 10 years for me to bowl my second 300 game. That was in 1992.”

Hufford competes in a national bowling tournament in 1994.

Since then, he has bowled 29 perfect 300 games, 21 800-series games and become a member of the Senior All-Star Bowling Association Hall of Fame and Mississippi State Bowling Association Hall of Fame.

Hufford has even earned some money from bowling – not a lot, just enough to make him wonder if he could have made a living as a professional bowler. So, after retiring, he plans to go bowling full time. He’ll leave Thursdays for places such as Las Vegas, San Antonio and Austin and return Tuesdays.

“I have eight to 10 bowling balls, so I can’t fly,” he said. “I’ll have to take my car.”

He will also make time to go to his grandsons’ baseball, basketball and soccer games. Clark said she hopes he will visit her “honey-do” list, too, and not buy any more bowling balls.

“I came home one evening to find the dishwasher running,” she said. “I was so pleased that Charlie had pitched in to do the dishes, only to discover when I went to unload it that the top rack had been removed and it was full of bowling balls.”

Hufford’s son, Gary, received bachelor’s and master’s degrees in aeronautics and astronautics and is head of AVEVA Inc.’s Visualization Center of Excellence in Huntsville, Alabama. Gary and his wife, Lori, a managing partner of StrateSoft LLC, have two children: Ryan, 16, and Andy, 13. Hufford’s daughter, Jennifer, who received bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UM’s nationally ranked School of Accountancy, is a tax director with Deloitte Tax LLP in Nashville, Tennessee.

Before retiring, Hufford said he hopes to check a few more things off his bucket list: install the pharmacy school’s new NMRs, finish construction of the west wing and get Faser’s second floor redone. Even if he doesn’t get to all of them, he leaves a legacy that will continue through future accomplishments of the school’s faculty, staff and students.

“One does not attain the laurel wreath of recognition through self-promotion but by working diligently for the common good,” said Baker, referring to Hufford.

|