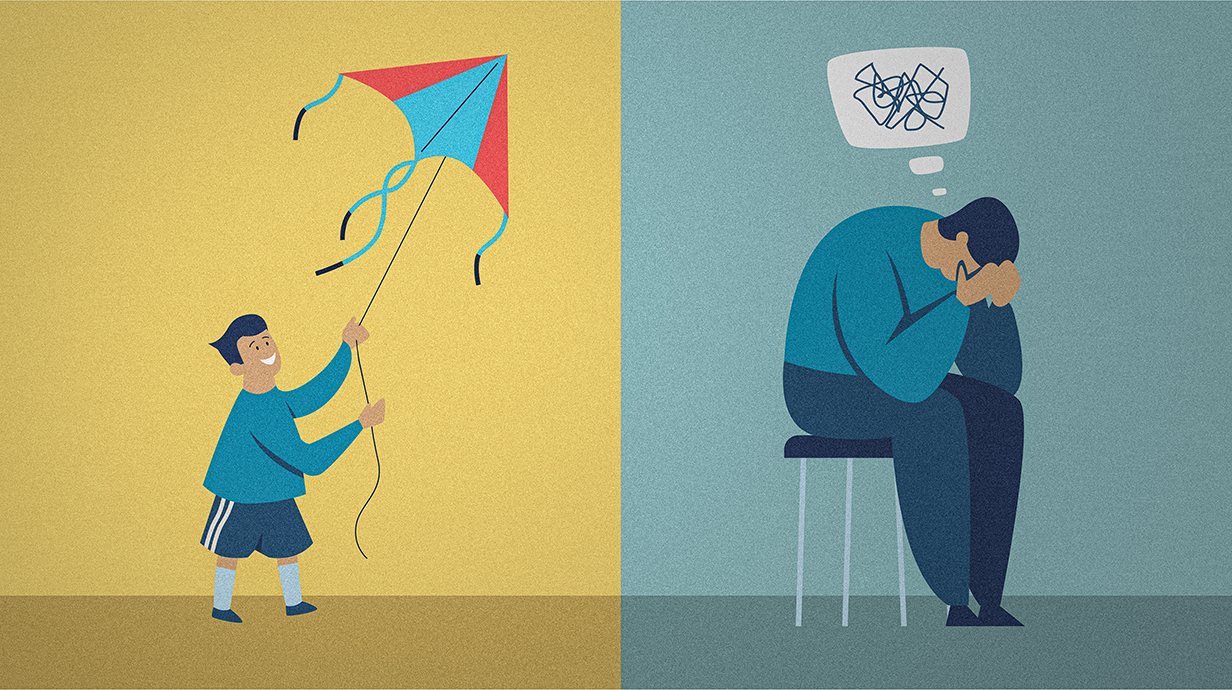

Punishment for Childhood Trauma Can Last a Lifetime, Researcher Says

Abigail Novak's recent publication says punishment for children who experience trauma can worsen effects

OXFORD, Miss. – When authority figures punish children for coping or adapting to trauma, it can affect the child for life, according to a new publication from University of Mississippi researcher Abigail Novak.

Novak, assistant professor of criminal justice and legal studies, used her expertise in childhood trauma and adverse experiences to examine Judith Harris's theories of child socialization. The Ole Miss professor's research has been published in the journal Developmental Review.

Punishing children for responding to traumatic experiences by acting out or withdrawing, for example, can reinforce damaging labels and alienate the child, she said.

"I went back to the drawing board, read her work again and figured out a road map about what Harris' work tells us about ACEs, or adverse childhood experiences," Novak said. "She was making a lot of arguments about labeling – labeling argues that when individuals respond in a certain way, in a deviant way, people label them as deviant and that label follows them.

"When we assign a child as good or bad, that shapes their peer groups, their experiences and their life."

Children who experience trauma are less likely to have positive relationships with the education system and less likely to graduate high school or pursue college. They are also more likely to be arrested and jailed and struggle with mental health, addiction and homelessness.

Childhood adversity also reduces life expectancy by 20 years, as those who experience it are more likely to experience heart attacks, strokes, obesity and other health complications.

Why childhood trauma affects people throughout their lives could be linked to how they adapted to their trauma, and how their authority figures responded to these adaptations, Novak said.

A child who experiences trauma – whether that be the death of a family member, physical or sexual abuse, or otherwise – develops adaptive behaviors that may protect them from their traumatic experience at home, but encourage labeling in the classroom, Novak said.

"When kids are little, they go through trial and error," she said. "That's child development broadly, and we know that this is what kids do. They try to do what they do at home in school.

"For kids who are exposed to trauma, they have adapted these maladaptive coping behaviors at home. If they go into the school environment and those behaviors are met with rejection, punishment, etc., that shapes the child."

If a child withdraws or acts out – both common child responses to trauma – they may be labeled as "quiet" or "bad." As a known "bad kid," they may not be considered for gifted programs or accelerated classes.

The child may then receive less attention from a teacher or mentor, or they may get constant oversight and punishment for these behaviors, alienating them further from peers, Novak said.

Punishing a child who is still learning to navigate complex social structures – such as being in a classroom filled with other children – only worsens the effect of childhood adversity, she said.

"For kids who are exposed to adversity, if they aren't given the chance to adapt their behaviors or given the resources to do so, they're going to experience rejection, which is going to have negative consequences for them down the road into adolescence, into adulthood," she said.

"Judith Harris is insistent that you don't need to change their behavior; you need to change their environment because their behavior is contingent on the environment. That's a large call for macro policy solutions, things that shift environments. It requires tons of political will, and it's hard to do."

Beyond such large-scale changes, however, more ground-level changes are possible that can improve children's lives, she said.

Novak recommends a national minimum age for arrest, arguing that below a certain age, children are not culpable and competent.

Mississippi's minimum age for arrest is 10; the United Nations and a handful of states have set the age as high as 14. But 24 states still have no minimum.

She also recommends eliminating suspension for children in kindergarten or preschool.

"There are smaller level policy changes that shift how we respond to kids that are behaving in an appropriate way to their chaotic environment," she said. "We can't always change environments, but we can shift our responses to make them less punitive."

Novak's article was published in a special edition of Developmental Review dedicated to Judith Harris' book "The Nurture Assumption."

By

Clara Turnage

Campus

Published

June 05, 2024