Researchers Urge Intervention to Save Coast's Oyster Reefs

Legislative, local action needed to rebuild Mississippi seafood industry

OXFORD, Miss. – Biloxi was once known as the oyster and seafood capital of the world, with a thriving economy of fishermen often visiting the Gulf Coast's oyster reefs daily.

Those reefs have been closed since 2019, and the oysters that built them are dying faster than traditional methods of regeneration can fix, University of Mississippi researchers said.

In their recent publication in the Journal of Shellfish Research, Deborah Gochfeld and Stephanie Showalter-Otts found natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina, manmade contamination including oil spills and freshwater dumping from spillways, and changes in water quality due to climate change are killing Mississippi oyster reefs.

"Previously, there was a hurricane that wiped (oyster reefs) out for a year or two, but then they would come back, or there was a flood that wiped them out for a period of time and then they would come back," said Gochfeld, a principal scientist in the National Center for Natural Products Research and research professor of environmental toxicology.

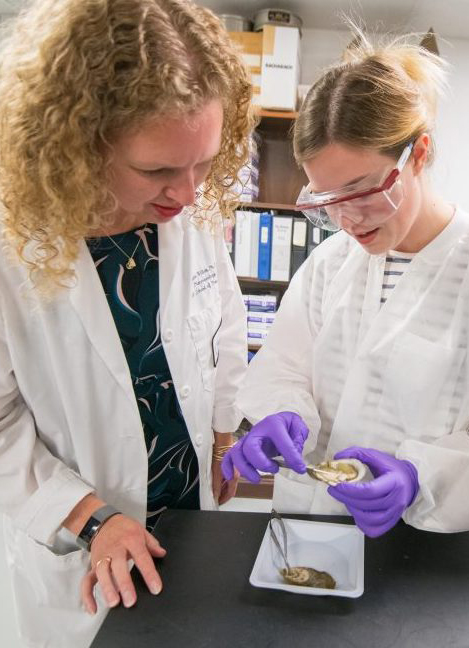

Kristine Willett (left), chair of the Department of BioMolecular Sciences, examines an oyster with Ole Miss student Ann Fairly. Willett is one of three UM researchers studying the factors behind the disappearance of oysters off the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Submitted photo

"But now you've got this continuing onslaught of human-made disasters like the oil spill as well as climate change hitting them from all different angles; there's only so much they can take. They really have lost their resilience or their ability to recover from those multiple stressors."

Besides the economic profit of oyster farming, oyster reefs provide crucial benefits to the ocean's ecosystem, such as filtering and purifying water, creating habitats for other ocean life and preventing coastal erosion.

"There was a time 100 years ago when the economy of the Gulf Coast was really driven by the oyster fishery," said Showalter-Otts, director of the National Sea Grant Law Center.

"There has always been a bit of a boom-and-bust cycle with oyster fisheries in Mississippi, but what we found is that (the reefs) normally could recover. Since the oil spill, we just haven't seen that type of recovery in part due to the impacts of the opening of the Bonnet Carre Spillway in 2020."

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers opened the Bonnet Carre Spillway twice in 2019 and for an extended period in 2020 to release floodwaters from the Mississippi River. This freshwater lowered the salinity of oyster fields in the Mississippi Gulf Coast and killing off younger oysters.

Previous restoration efforts often included closing a reef off to anglers to allow it to recover and dumping oyster shell substrate into the area to help the population regenerate. Those efforts work to revive a reef that is struggling but will not resurrect an oyster population that is dead.

"We really need to use science to inform restoration decision-making," Gochfeld said. "If you put the substrate out in a place where (the oysters are) not going to survive, you're wasting your time and money."

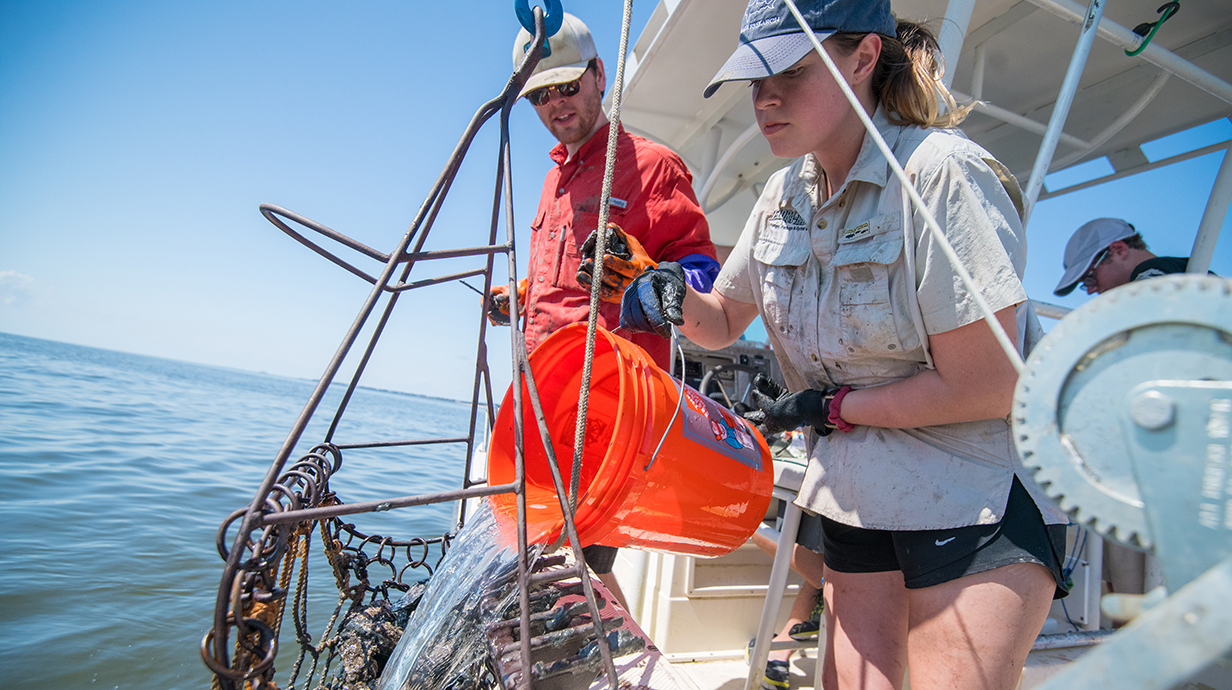

The researchers studied the early life cycle of oysters to understand what caused the young oysters to die and to discover how to help regrow the population.

"We were really interested in what happened to early life stages because the Mississippi Sound, in particular, has been exposed to more and more of these flood events between climate change and increasing storms and increasing precipitation in different places," Gochfeld said.

Deborah Gochfeld"It's not even just what happens right here on the coast. It's what happens in Illinois and Michigan and all these other parts of the country that affects what happens downstream."

Adult oysters can close their shells temporarily and are more resilient to changes in water quality and temperature. Larval oysters, however, are much more susceptible to stressors than adult oysters.

Healthy reefs have enough mating adult oysters to replenish any lost offspring, but when the adults are being harvested and the young killed by stressful environmental conditions, the reefs die.

Researchers recommend growing oysters in tanks and hatcheries until they are old enough to withstand more stressful conditions before transplanting them back to the old reefs. This would help rebuild the population of adult oysters that can withstand more environmental change.

"One of the policy recommendations is that the decision-making tools that the agencies are using need to incorporate more information about all of the life stages of oysters," Showalter-Otts said.

"Another of the recommendations would be to allow the oysters to stay in the hatchery longer before moving them offshore to restoration reefs so they can withstand different conditions."

Replacing the lost adult population will not make lasting change, however, unless we change how well humans steward the ocean, she said.

"We need to know how oysters are moving in the Gulf of Mexico and how the freshwater intrusions like the discharges from the Mississippi River are affecting water quality," Showalter-Otts said.

"There is a lot of modeling around water quality or temperature based on survivability of adult oysters, but our recommendation is to factor in the survivability of different life stages when they are implementing projects to place oysters on restoration reefs."

Other recommendations include limiting spillway activities during oyster spawning periods, moving oysters ahead of intended spillway activity, and reducing the regulatory hurdles that come with oyster aquaculture farming.

"Globally, oyster reefs have been in decline and the Gulf of Mexico has been actually one of the last places that was supporting wild harvest oyster fisheries," Showalter-Otts said. "This absolutely is a human issue."

By

Clara Turnage

Campus

Published

June 12, 2024