Farm Waste Can Filter Microplastics in Runoff, Prevent Pollution

Researchers find biochar reduces microplastic pollution in agricultural runoff by more than 92%

OXFORD, Miss. – Using treated plant waste as a filter reduced the presence of harmful microplastics in agricultural runoff by more than 92%, according to a new study authored by a University of Mississippi research team.

Microplastics – tiny plastic particles that are smaller than 5 millimeters – have been found in every ocean on earth, in food, water, and recently, in farmlands. An Ole Miss-led research group has published proof-of-concept data that shows biochar to be a cost friendly and effective method of filtering microplastics from overland water runoff.

Biochar is a type of charcoal made from plant material that has been heated or burned in an oxygen-limited environment.

Boluwatife Olubusoye, a doctoral student in chemistry, collects a sample of agricultural runoff water. Submitted photo

"Microplastics in the environment stem in part from the degradation of larger plastic by natural physical, chemical and biological processes," said James Cizdziel, professor and interim chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

"They pose an enormous challenge as they are widespread, persistent and can accumulate in plants and wildlife, leading to detrimental effects on certain organisms and, potentially, on humans who consume them."

Microplastics have been found in humans and the part of human brains responsible for smell. Though scientists don't yet know the effects of microplastics on the human body, many studies show that the plastics negatively affect fish and animals that ingest them.

Microplastics in agriculture come from two primary sources, said Boluwatife Olubusoye, an Ole Miss doctoral student in chemistry and an author of the study. Sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants, which is used as a fertilizer, and plastic mulch and row covers, which insulate plants and promote growth, both bring measurable amounts of microplastics to agricultural areas.

"When these plastic sheets break down in the field, they become very tiny and that's how you get microplastics in the agricultural fields," the Lagos, Nigeria, native said. "What happens is that when there is a heavy rainfall, there will be a wash of this agricultural field, which can lead to agricultural runoff.

"And this runoff can transport microplastics, and other pollutants, from the farm into aquatic environments – such as rivers, lakes and oceans – where microplastics can pose threats to organisms like oysters and small fishes."

Many animals, including humans, feed on such organisms, where the microplastics could be passed on.

Olubusoye and collaborators from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Water Quality and Ecology Research Unit in Oxford traveled to a farm near Beasley Lake in the Mississippi Delta to collect agricultural runoff.

They tested the water for microplastics in Cizdziel's microplastic research laboratory at Ole Miss, and passed the runoff through biochar to determine how effective it was at capturing the microplastics.

"We also observed that in addition to agricultural runoff, urban stormwater runoff is a prominent source of microplastics pollution," Olubusoye said. "Our research is trying to reduce the influx of these contaminants from these runoff events into downstream water bodies."

Using biochar reduced the amount of microplastics in samples of runoff by between 86.6% and 92.6%. Because of the success of the initial tests, the researchers are scaling up efforts to test biochar in the field.

The researchers will present their findings at three upcoming conferences, including:

- The University Council on Water Resources, National Institute of Water Resources and American Water Resources Association Conference

- The Mississippi Water Resources Conference

- The Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

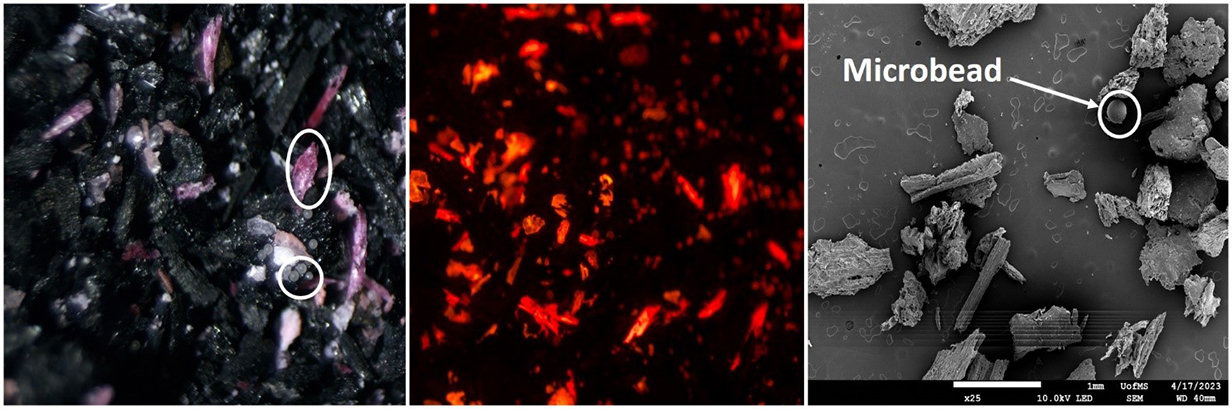

A microscopic look at biochar shows microplastic particles that were caught and removed from agricultural runoff in the Mississippi Delta. Submitted photo

"Our findings underscore the potential of biochar to be a cost-effective adsorbent for the removal of microplastics from runoff," Cizdziel said. "As such, scaled-up field studies are underway and preliminary data show a marked decrease in microplastics, including tire wear particles, after the runoff passes through large filter socks filled with biochar.

"Our work could result in new agricultural and stormwater management practices to mitigate microplastic pollution stemming from farms and urban runoff in order to safeguard environmental and human health."

This material is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation grant no. MRI-2116597 and the National Institutes of Health award no. P20GM103460.

Top: Boluwatife Olubusoye, a doctoral student in chemistry, places bags of biochar, or specially heated biowaste, at the head of a runoff tunnel. Olubusoye and a team of Ole Miss and USDA researchers found that biochar can filter more than 92% of microplastics from runoff water. Submitted photo

By

Clara Turnage

Campus

Office, Department or Center

Published

October 09, 2024