UM Research Indicates Stuttering Is More Than a Speech Disorder

Emerging science suggests the condition may be part of a broader disease process

OXFORD, Miss. – Many people consider stuttering just a simple speech disorder. But University of Mississippi professor Gregory Snyder and a team of student researchers are working to upend that thinking and develop new ways of treating it as a complex central nervous system disorder.

Snyder, an associate professor of communication sciences and disorders, has studied stuttering and related language disorders for decades, both personally and professionally. His research indicates that stuttering affects not just spoken language, but also sign language and handwriting, suggesting a broader neurological basis.

While stuttered speech has many different underlying causes, including neurological, autoimmune and streptococcal involvement, Snyder's work builds on earlier findings that link stuttering to genetic mutations. Some of these mutations overlap with a serious childhood disease.

The results could lead to earlier diagnosis and better treatments for the condition.

"Once you open your mind to what stuttering could be, it becomes so much more clear," the Ole Miss researcher said. "Stuttering behaviors represent a failure to initiate and transition between automated linguistic gestures, and once my mind came open to that, then I started to do all of this other research."

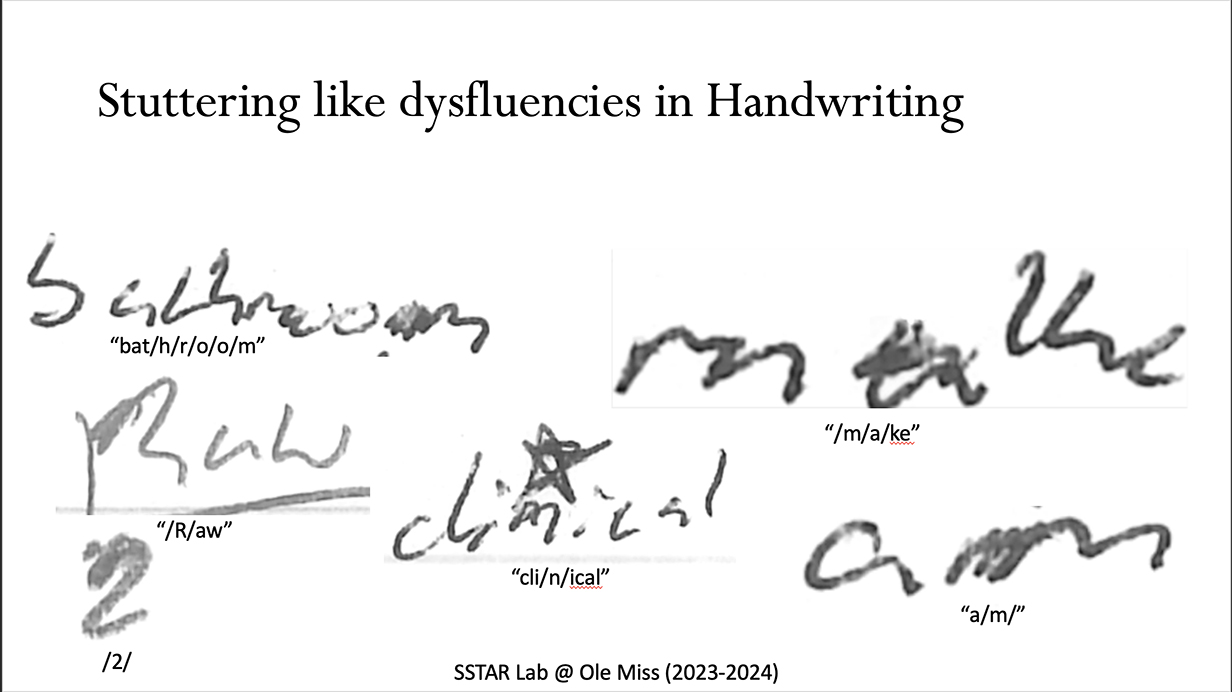

Stuttering is not confined to speech; handwriting can show signs of disfluencies with partial stroke repetitions, prolongations and hesitations. These patterns reflect the same difficulty in starting or continuing linguistic movement seen in speech and sign language. Image courtesy UM Laboratory for Stuttering: Science, Treatment, Advocacy and Research

More than 3 million Americans – about 1% of the population – stutter, according to the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Stuttering can affect individuals of all ages but occurs most frequently in children between the ages of 2 and 6. Boys are two to three times more likely than girls to stutter.

Current stuttering assessments rely on observation and self-reporting, using the CALMS model to evaluate awareness, emotions, word avoidance, speech patterns and social impact, Snyder said. No biological tests are available and treatments have changed little over time, aside from limited use of medication to reduce dopamine activity.

Snyder and his team of undergraduate and graduate students are conducting a small study examining vitamin supplementation as a potential treatment.

"All dosages used are below the daily recommended value," he said. "This is a pilot study, and we've enrolled about a dozen participants thus far, so we're still in the early stages of developing the research paradigm."

By analyzing the urine of test subjects to evaluate their neurological function and gut health, Snyder discovered that biological markers may help predict which patients will respond best to stuttering treatments.

"What we're trying to do is supplement the nervous system to help it function better, allowing the brain to compensate optimally," he said. "While traditional therapy adjusts speech behaviors as a stopgap, it's more effective to address the underlying brain mechanisms where stuttering originates."

The results revealed consistent patterns: all patients experienced significant gut health issues, reduced absorption of antioxidants and low levels of amino acid metabolites. From this, Snyder concluded that stuttering is not just a speech disorder, but rather a larger medical condition with speech disfluencies as its most visible symptom.

"Via improved gut health and vitamin-mineral supplementation of the neural functioning, we are allowing the patient's body to better compensate and correct for the stuttering disease at the cellular level," he said. "This, in turn, makes the very act of speaking easier, as well as potentially significantly enhancing fluency and likely improving other unrecognized symptoms of the stuttering disease."

Snyder said the findings were somewhat serendipitous. His team was using organic acids testing to assess treatment response and noticed that individuals who stutter appeared to have a distinct pattern of values.

This may be the first time such data has been collected, he said.

"The patients in a double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study have told me, 'I knew it was working, because when I stop taking it, my life got harder,'" he said. "'Every time we (people who stutter) speak, it takes concentration and effort, but when we follow this supplementation regimen, the act of talking becomes easier.'"

"That's why simply counting stuttering episodes isn't the best way to measure success. A better question is, 'How much effort does it take for you to talk in general?'"

Many mainstream approaches to treating stuttering focus on suppressing stuttered speech based on the assumption that it is harmful and serves no purpose, Snyder said. However, a growing number of stuttering researchers recognize that it is better to work with the body and stuttering behaviors, as opposed to suppression.

"Many people who are disfluent do not speak," said Dee Lance, UM professor and chair of communication sciences and disorders. "They don't have time to speak because it takes more effort for them to communicate, so they are in a room full of people and isolated because they don't get the opportunity to share their opinion, especially if the discussion is fast-paced."

This study of the metabolic theory of stuttering is a cutting-edge project, one that reflects the mission of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Lance said.

"Fluency has been something that we aren't always successful in treating; this is one of those areas that needs work," she said. "Communication disorders are the most personal of all disabilities, to be not able to talk or to engage is very isolating,"

Snyder hopes his work paves the way for future advancements.

"Once the biological factors of stuttering are better understood through science, we hope to create targeted noninvasive assessments that result in customized effective behavioral and medical treatments for each child and adult within the stuttering community" he said.

Top: Ole Miss professor Greg Snyder and his team are investigating the underlying causes of stuttering in hopes of developing effective treatments for the condition. The team includes (from left) Faith Patton, a master's student in communication sciences and disorders; Allison Akers, an Ole Miss senior; Snyder; Makayla Montgomery, a junior; and Madilyn Morris, a master's student. Submitted photo

By

Jordan Karnbach

Campus

Office, Department or Center

Published

June 04, 2025