Study Explores Link Between Stress and Addiction Risk

Social stress alters brain's reward response, increasing likelihood of substance abuse

OXFORD, Miss. – Extreme instances of stress can cause lasting changes to the brain itself. This could leave some people more vulnerable to addiction, a University of Mississippi study concludes.

Science has long associated stress with risk of substance misuse, but the Ole Miss study may have found a reason for the connection. Alberto Del Arco Gonzalez, associate professor of health, exercise science and recreation management, and Yixin Chen, chair and professor of computer and information science, published their results in the Society for Neuroscience's eNeuro.

The study's insight could explain why some people are more vulnerable to substance use disorders and point toward better prevention or more targeted treatment.

"After that experience of repeated stress, something is changing in the brain," Del Arco said. "Stress is a physiological response. We are supposed to stress from time to time and then recover from it.

"But this kind of repeated, intense stress produces effects that might persist for a long time. This is what is important because this can be the starting of a transition from a healthy brain to a brain with an addiction, substance use disorder or another psychiatric disorder."

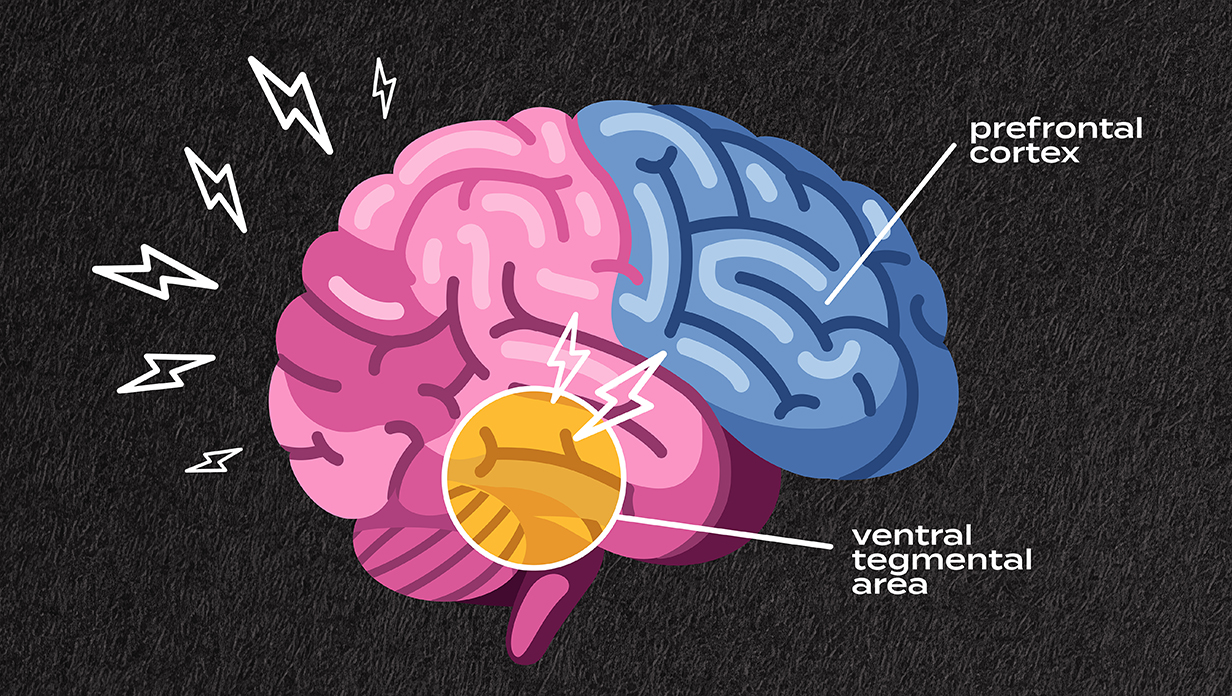

The research team used animal models to study two parts of the brain: the prefrontal cortex, known as the decision-making center, and the ventral tegmental area, which influences motivation and the drive to seek rewards.

After a series of stressful events, activity decreased in the prefrontal cortex, potentially making the brain less able to make informed decisions. At the same time, activity in the ventral tegmental area increased, causing a spike in the desire for a reward.

In short, stress could make risky behavior such as substance misuse more tempting and harder to resist.

"The idea is that these processes make you more prone to escalate in substance use," he said. "Stress decreases the percentage of people who can just walk away from drugs and increases the risk of developing substance use disorder."

The project required Del Arco to parse through a vast amount of data. Over the course of a year, Chen oversaw a team of undergraduate students who developed and tested a machine learning algorithm to do just that.

Involving students from the computer science and data science majors offers" researchers a way to create custom machine learning programs for their study while providing students with a real-world application of what they learn in the classroom, Chen said.

"It's really a win-win situation," he said. "Our students are looking for real-world problems, and this project gave them that opportunity while supporting important scientific research."

The team studied both the long- and short-term changes in the two areas of the brain. Activity in the prefrontal cortex can stay diminished for at least two weeks, meaning decision-making processes could remain impaired for a long while.

In contrast, activity in the ventral tegmental area actually drops below normal in the weeks following repeated stressors, suggesting what Del Arco called a "reward deficit."

"This deficit could be related to the idea that the same reward is no longer enough to satisfy the craving," he said. "This could make someone more prone to escalating substance misuse because they can no longer get the reward."

Both the initial response of the two areas in the brain and the long-term impact of stress could contribute the development of substance use disorder.

"We know that stress is associated with a higher risk of developing substance use disorders, but we don't know how," Del Arco said. "These data explain how that happens by looking at the neuronal response to reward cues after stress.

"Knowing more about the biology of vulnerability – in this case, stress-induced vulnerability – can help us not only prevent addiction but also treat it better."

This material is based on work supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through National Institute of General Medical Sciences' Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence grant no. P30GM122733.

Top: A recent study by Ole Miss researchers indicates that the brain responds to repeated instances of stress in lasting ways. Some of these reactions could make people more susceptible to substance abuse. Graphic by Jordan Thweatt/University Marketing and Communications

By

Clara Turnage

Campus

Office, Department or Center

Published

September 29, 2025