The enslaved man George worked as a janitor at the University of Mississippi and was employed by the Phi Sigma Society, one of the antebellum literary societies students at the University of Mississippi were required to join.

George first appeared in the board minutes on July 12, 1849, when the board recognized George, “for performing his duties in a faithful manner,” and gave him “a present” of five dollars for the work he performed during the academic session, approximately nine months. Four years later, on July 13, 1853, George was referenced again. “On motion,” the minutes state,“it was ordered that the [account] of Dr. [John] Millington for services of servant George as janitor be allowed by deduction the time he was sick, and that the Proctor pay the same.”

As a janitor, George’s responsibilities included chopping wood, building fires in each of the buildings each morning, transporting water, and cleaning the dormitories and classrooms.

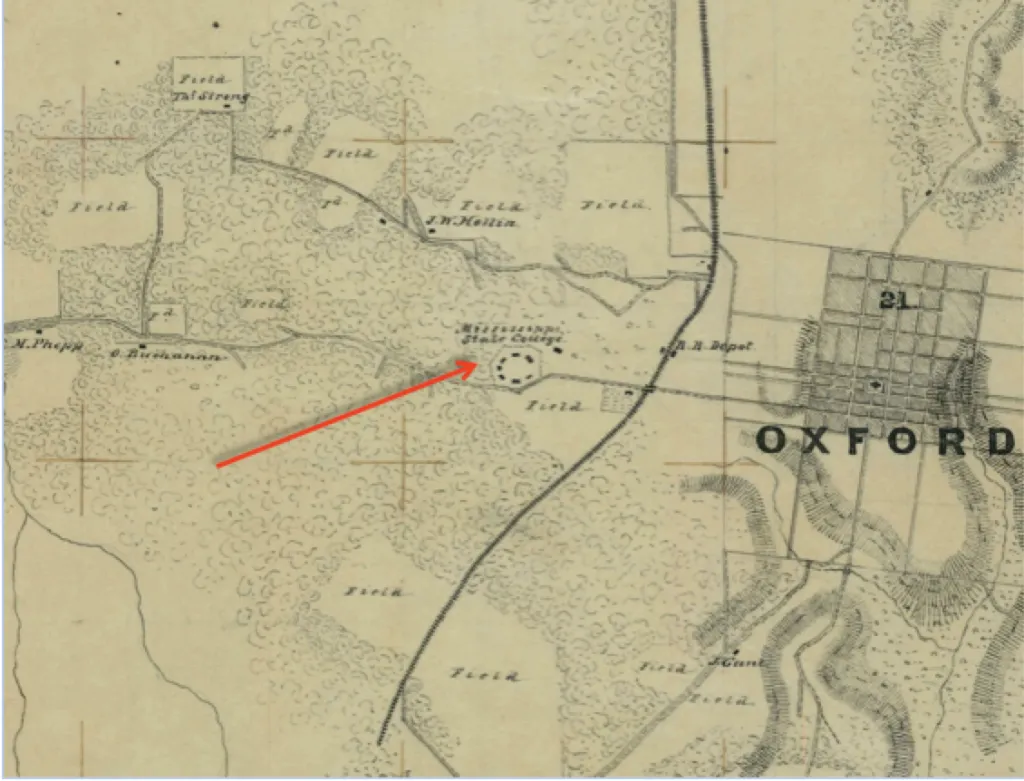

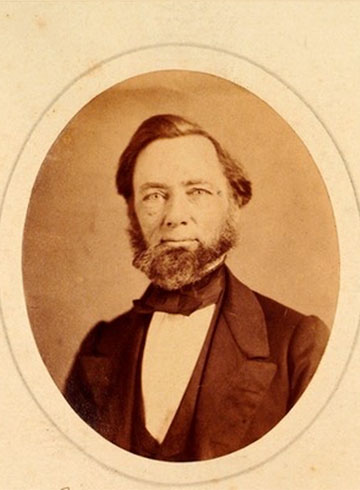

Given that John Millington, a University of Mississippi faculty member was paid for George’s work, Millington was almost certainly his master. It is likely that George was one of two men–aged 53 and 40–owned by Millington in 1850 and recorded on the 1850 slave schedules.

In addition to the work he did for the University as a whole, George was also one of three slaves employed by Phi Sigma before the Civil War. He worked for the society from approximately May 1849 to November 1849.

The meeting minutes maintained by Phi Sigma indicate that the enslaved men the society hired performed a variety of tasks, including attending the hall, sweeping the floor, cleaning the spittoons, disposing of trash, bringing water for the meeting, and making fires when necessary.

More information about the work enslaved laborers did on behalf of the Phi Sigma Society can be found here.

See Journal of the Board of Trustees, 1845–1860, Florence E. Campbell Transcription, [page numbers needed]. Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi; Phi Sigma Debate Society Meeting Minutes, May 26, 1849, September 29, 1849, November 3, 1849. Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

Profile written by Andrew Marion and Anne Twitty